Food and energy supply chain constraints pushed up prices post-COVID. So, what does the future have in store for us?

According to the International Monetary Fund food and energy are the main drivers of today’s inflation. As we all find ourselves increasingly spending more money on food and heating bills, it is hard to deny this fact. In this article we compare food price inflation across Central and Eastern Europe in the 18 countries where GrECo Group operates and ask how differences in prices came about, and what the consequences are for insurance?

How food price inflation is measured

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation uses the Food Price Index (FFPI) to track and monitor price changes in international markets for key basic foodstuffs. They use the reference period 2014 to 2016 as the FFPI base value, this being 100. For example, if in July 2005 the FFPI in Austria was 76.4, this means that the main basket of food products cost 23.6% less in July 2005 than the average basket in 2014 – 2016 yy. If the FFPI, let’s say, in June 2022 was at 121.1, the food inflation was 21.1% compared to 2014 – 2016 yy.

Different rates of food price inflation in Europe

For the purposes of this article, we analysed the food price indices in CEE/SEE countries. These are split into the following three groups: EU countries using the Euro as an official currency, EU countries using their own national currency, and non-EU countries.

The analysis shows that the increase in food prices in EU countries follows the same course, i.e. the dynamics from 2020 are very high compared to the previous 20 years (2000 – 2019 yy). This proves the economies of EU countries are interconnected.

Trends of note

For countries outside the EU, we see that prices have risen in different ways at different times.

There was a sharp increase in prices in 2013 – 2014 in the Ukraine, which can be attributed to the destabilisation of the economy during the Maidan Revolution, the ensuing Russian occupation in February 2014, and the subsequent large devaluation of the local currency.

If we look at the period 2020 – 2022, a more interesting trend can be seen primarily related to COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Among the six Euro area countries we analysed, Austria showed the lowest FFPI increase and Lithuania the highest. Furthermore, among the five EU countries that use national currencies, the highest inflation was recorded in Hungary, and the lowest in the Czech Republic. Meanwhile,among the four non-EU countries, Ukraine suffered a much higher FFPI than in the period 2014 – 2016. Serbia is the most stable in this respect.

A look at increasing food prices during 2020 – 2022

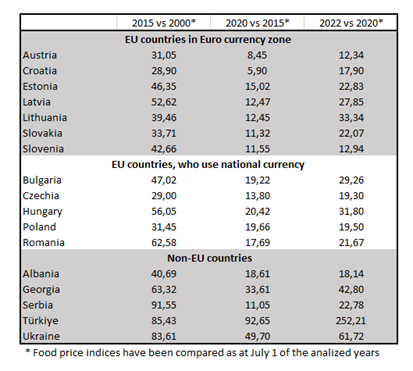

The table below clearly illustrates the differences between countries because it allows for a better comparison of FFPI values at different points in time during recent periods. For example, the column 2022 vs. 2020 shows the percentage increase in food prices on 1 July 2022 as compared to 1 July 2020.

The table also shows that inflation in the period 2022 – 2020 yy was twice as high as in the period 2020 – 2015 yy in almost every country. We can see that prices started to increase drastically from the third and fourth quarter of 2021. We therefore believe that the root cause was the post-COVID food and energy supply chain crisis.

Why is food price inflation so high between 2020 – 2022?

A fundamental cause of any inflation is the scarcity of goods, either their total lack or their availability in only insufficient quantities. This happened in the post-COVID recovery phase, when deferred demand for energy resources collided with supply chain constraints. At the same time, in 2021, we witnessed a sharp increase in the prices of cereal and oilseed raw materials. We also saw the first forecasts of increasing food prices. Soon thereafter, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to a new problem in the food supply chain – the disruption of grain exports from Ukraine, which is one of the world’s largest grain producers. This disruption, which is still ongoing, has undermined global food insecurity, leading to increased prices and shortages in many regions.”

Another cause of inflation is excess demand, be it due to the government printing extra of money, the acceleration of the money multiplier, new demand created by GDP growth, or the inflow of new foreign capital. For example, according to Forbes the consistent monetary stimulus on a massive scale, unprecedented since World War II, turned the flywheel even further in 2020 – 2022.

On top of that, the negative expectations of enterprises and consumers add more fuel to the fire. Today, nobody is willing to take a risk by selling goods without hedging against the risk of higher production costs in the future. Manufacturers are already increasing prices to transfer the risk to their consumers. There is also the theory that big corporations and monopolists (e.g., in the energy segment or food retail) can merely squeeze out more profit by driving up prices. It will be interesting to see what the final 2022 balance sheets and ESG reports will look like for 2023.

Impact of inflation on insurance markets

In our opinion, inflation impacts negatively on insurance consumption and insurance premiums. On the positive side, greater financial uncertainty, and changes in the spending structure (increased share of spending on inflexible goods and utilities) make households and enterprises rethink their insurance spending.

To further curb price increases, central banks significantly raise base rates. Together with inflation expectations and the calculation of an additional risk premium for uncertainty, such actions lead to a significant increase in the cost of capital. This means investors in the insurance industry are increasingly making outrageous demands.

As a result, we have already witnessed a lack of capacity following the first wave of investor capital outflow from international insurance markets. As a result, insurers are not only starting to optimise their portfolios, but they are also becoming increasingly risk averse. Some of the conventional property risks are very difficult to renew and additional limits, for example, in the meat industry, in agricultural insurance, and in other sectors can hardly be obtained. Markets are thus hardening again.

What can we expect in the not-too-distant future what will save us from the abyss?

Food and energy supply chain constraints pushed up prices post-COVID. Aggressive government monetary policies, negative expectations and further supply chain disruptions caused by Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine exacerbated the situation. This has affected CSEE countries in different ways, however what they have in common is that prices in 2021 – 2022 soared at an unprecedented rate. The insurance market, in turn, is now entering a phase of portfolio optimisation due to the growing lack of investor capital.

So, what does the future have in store for us?

A similar scale of inflation took place in the 1970s when price increases were associated with oil shocks in 1973 and in 1979 – 1980. That said, prior to these shocks, monetary policy was focused on keeping interest rates low to maintain employment levels and pour more money into an economy that resembles ours today. Further policy tightening resulted in a deep economic crisis in the early 1980s.

However, there are two important differences between the current situation and the 1970s. The first is that the magnitude of commodity price jumps today is smaller than in the 1970s. And the second is that a paradigm shift in monetary policy frameworks has taken place since the 1970s, meaning central banks in advanced economies now have clear mandates for price stability, which is expressed as an explicit inflation target.

Beyond the near term, inflation is expected to decline, but the experience of the 1970s suggests some material risks to this inflation outlook.

The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR – www.cepr.org )

CEPR considers such risks to be material if the following events do not occur:

1. Global production lines and logistics undergo adjustments.

2. Inflation expectations are expected to stay firmly anchored in the medium term.

3. The structural forces that suppressed inflation prior to the pandemic endure.

In addition, we believe increasing economic activity towards the reconstruction of Ukraine and new investments in technologies leading to the decarbonisation of economies will additionally inject economic growth, which will, in turn, result in a stabilisation of prices.

Sources consulted:

https://www.fao.org/datalab/website/web/food-prices

https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgecalhoun/2022/09/30/what-is-really-driving-inflation-today/

https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/CP

https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/09/09/cotw-how-food-and-energy-are-driving-the-global-inflation-surge )

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/todays-inflation-and-great-inflation-1970s-similarities-and-differences

Insured by Algorithms

The insurance industry is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the rapid adoption of AI and predictive analytics.

Beyond Moving Cargo: Why Employee Well-Being Is the Real Asset in Logistics

In today’s employee-driven market, especially for Gen Z talent, benefits aren’t just perks – they’re strategic tools for attraction and retention

The New Edition of FORWARD Magazine Is Now Available

GrECo is proud to present the latest edition of our client publication, FORWARD Magazine—now live and ready to explore.